A shark fossil that has been sitting in the basement of the New Brunswick Museum since it was found near Campbellton in 1997 could change science's understanding of the evolution of vertebrates.

That's because it is the oldest shark specimen known to have teeth inside its jaw.

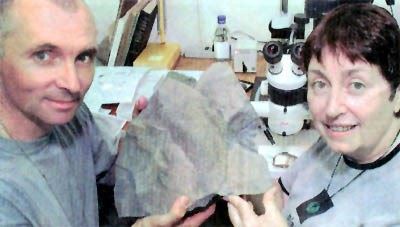

Dr. Sue Turner, a vertebrate paleontologist with the Queensland Museum in Australia and an expert in shark fossils and early fish, arrived this week to study a complete shark fossil discovered more than five years ago near Atholville. It, is the oldest in the world and dates back 430 million years to the Devonian Age.

"It was a time when our ancestors, the fishes, really got going," she said.

A fossilized shark tooth is seen inset here.

Dr. Turner is studying at the museum for two weeks on a research grant. She said the discovery of an intact shark skeleton, a Doliodus problematicus less than one-metre long, indicates both the environment and the rock that housed the fossil were quite special.

"We think this rock is probably mud from a lagoon.

It's very, very fine grained, and, probably it was quite a warm lagoon on the edge of the sea," she said.

Past findings have included single teeth and scales because sharks are. mostly made of cartilage, something that doesn't preserve well, Dr. Turner said.

"Sharks are quite rare in the fossil records," she said.

"Certainly complete ones are very very rare."

Since shark physiology has'nt changed much over time, Dr. Turner said the fossil opens new doors for research and speculation because it proves shark fins once had spines.

"It's quite unusual," she said. Up to now her field was unaware that any sharks had spines in their pectoral fins.

"Certainly it could probably change the ideas of how we think of vertebrate evolution," she said.

"Because already it's telling us that one idea we had about sharks, that they didn't have fin spines on their paired fins, is wrong.

" Because ancient fish were thought to lack jaws, and instead had cartilage supporting their bronchials regions, with scales all over their mouths, Dr. Turner said the specimen could help scientists understand why humans still have teeth.

"We're really at the moment trying to understand how teeth evolved.

"Originally there were lots and lots, of teeth in the jaw of a fish, and now we (as humans) are restricted to very few.

"And we have a very short jaw that is getting shorter."

It also proves teeth really haven't changed much in about 400 million years since they evolved from scales.

"Before this ... we don't even have any teeth shown in succession."

Dr. Randall Miller, curator of geology and paleontology of the New Brunswick Museum, said having Dr. Turner on hand to explain the significance of the fossil has been extremely important.

"It's great to have someone like Turner here because we have fossils of a wide range in New Brunswick and my expertise is in one group of fossils and there's no way that at the museum we can study in detail the wide variety that we see," he said.

Dr. Miller studies Ice Age beetles, which only date back about 100,000 years.

Find more article's like this by clicking here:

0

Log In or Sign Up to add a comment.- 1

arrow-eseek-eNo items to displayFacebook Comments